Through the Base Realignment and Closure (“BRAC”) process, successive Administrations in the post-Cold War era sought to increase efficiency and cut costs in the Department of Defense by closing and realigning military bases. For the 1990s economy of the Inland Empire of Southern California, the closures of Norton AFB (San Bernardino) and George AFB (Victorville), followed by the downsizing of March AFB (Riverside Co.), meant the loss of $3.1 billion in total economic activity and 27,400 civilian jobs. The Riverside-San Bernardino MSA was thus the region of the country most adversely impacted by the early BRAC, a severe blow to an area already afflicted by high unemployment rates, low incomes, and declining property values, all helping explain why one-third of San Bernardino residents were on public assistance.[1]

The former Norton AFB had served as an aircraft and missile logistics depot, tasked with maintenance and support, supplies, and heavy lift transport, and as a consequence its 2,000 acres of developable industrial and commercial space and FAA-approved tower held out promise as a civilian commercial asset. The local base reuse authority, the Inland Valley Development Agency (“IVDA”), was challenged with determining how to transform the location to productive civilian use, which would require substantial investments in roads with connections to interstate freeways, demolition of outdated buildings and asbestos removal, and replacement of electrical, natural gas and telecommunications infrastructure. However, BRAC did not include the funding needed for redevelopment, nor did IVDA then have abundant other resources. Into this void $650,000 was lent to IVDA by a partnership associated with a designated regional center in the EB-5 investor visa program, providing the seed funding that enabled IVDA to obtain a matching $1.8 million infrastructure development grant from the U.S. Department of Commerce Economic Development Administration. This seed funding for infrastructure led to the rehabilitation of light manufacturing buildings with new electrical wiring, fire sprinkler systems, and roofing as well as street access ways and asbestos removal. These core infrastructure investments paved the way for transformation of the former Norton AFB.

Infrastructure, its current state or the need to invest in it, is very much in the news coming out of Washington as the current Administration seeks to pump money into the economy in ways that yield both near- and longer-term benefits. “Hard” infrastructure, generally, refers to the physical systems like roads, transportation, water, sewage, electric, and communications that form the backbone for a developed economy. The framework of “critical” infrastructure provides a somewhat different lens, focusing on the assets, systems and networks (as in the energy sector, information technology sector, waste and wastewater systems, to name a few) that are vital to the interests of the United States. Their incapacitation would jeopardize security, national economic security, national public health or safety. Funding sources of infrastructure development vary considerably and increasingly involve a public-private partnership (“P3”). Questions concerning sources of funding often run into the public vs. private and federal vs. state debates. Certain infrastructure development has identifiable funding sources, as in user fees and tolls for transportation and gasoline taxes for roads maintenance, while other infrastructure classes do not have standard sources. Where P3s exist, the added consideration of private ownership of infrastructure assets may surface as a political challenge.

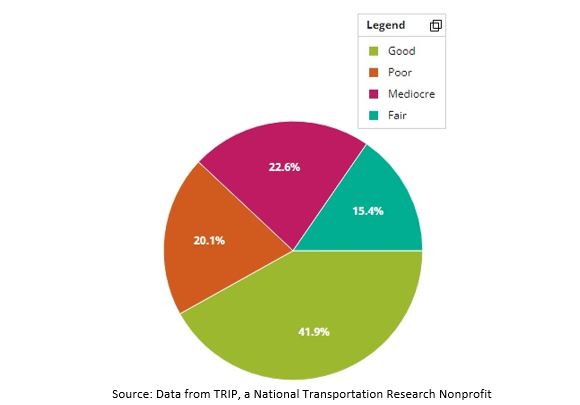

By one professional estimate, from the American Society of Civil Engineers (“ASCE”), the state of overall infrastructure in the United States is a grade “C-“, with for example a “D” grade for just the roads infrastructure.[2] ASCE has been sounding this alarm for many years. A full 43% of public roadways are rated in poor or mediocre condition.

By one professional estimate, from the American Society of Civil Engineers (“ASCE”), the state of overall infrastructure in the United States is a grade “C-“, with for example a “D” grade for just the roads infrastructure.[2] ASCE has been sounding this alarm for many years. A full 43% of public roadways are rated in poor or mediocre condition.

The backers of infrastructure-based legislative packages under consideration in Washington, with more than $600 billion allocated for infrastructure upgrades to roads, bridges, railways, airports and water systems, tout the needs of public health and safety, economic health and competitiveness, and national security.[3] The allocations for in-home medical care for the elderly and disabled push the price tag beyond the $1 trillion level.

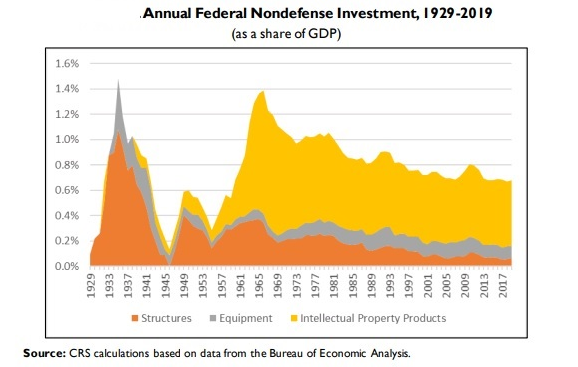

The political focus on investment of public funds in infrastructure appears to arise out of a consensus that America’s infrastructure has been neglected to the detriment of public welfare. That consensus seems to coalesce around data on declining public sector investment as a share of GDP.

ASCE observes, as further confirmation of the consensus, that since 2010 some 37 states have raised their gas tax to increase funding for transportation infrastructure, and in November 2020 balloting 98% of local infrastructure ballot initiatives passed. There also is recognition that infrastructure investments enable more private sector investment, production and efficient delivery of services. Over the longer term, the positive effects of infrastructure investments are realized: The more private sector investment into infrastructure projects, the better for the economy.[4]

ASCE observes, as further confirmation of the consensus, that since 2010 some 37 states have raised their gas tax to increase funding for transportation infrastructure, and in November 2020 balloting 98% of local infrastructure ballot initiatives passed. There also is recognition that infrastructure investments enable more private sector investment, production and efficient delivery of services. Over the longer term, the positive effects of infrastructure investments are realized: The more private sector investment into infrastructure projects, the better for the economy.[4]

Funding for roads and bridges historically involved the Highway Trust Fund, which depends on fuels tax revenues that are declining due to the static rate of tax, inflation, and improved fuel economy of automobiles. The Fund is no longer the one-stop formidable funding source it once was. State and local sources, consequently, are actually funding most highway expenditures. Transit systems, meanwhile, rely on fare revenue for at least 1/3rd of operating expenses, and the federal share is barely 7%.[5]

It is against this backdrop that the Pennsylvania Turnpike Commission (“PTC”) turned to EB-5 immigrant investor capital as a funding source. The PTC, an independent agency of the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, is entrusted with constructing, operating and improving the state’s turnpike highway system. While the PTC may fund much of what it needs for capital projects with the proceeds of senior revenue bonds that are secured by toll revenues collected by the Pennsylvania Turnpike, the PTC borrowed more than $380 million from partnerships formed by the Delaware Valley Regional Center (“DVRC”). This funding enabled PTC to efficiently pursue the construction, design and improvement of 130 miles of the Pennsylvania Turnpike, including the replacement or rehabilitation of various bridges, tunnels, and interchanges, and the enhancement of roadway safety.

In another example of EB-5 capital funding critical infrastructure, $180 million in funds lent by a separate DVRC-organized partnership to the Southeastern Pennsylvania Transportation Authority (“SEPTA”) helped fund transit infrastructure and vehicle improvements. Using EB-5 capital alongside other local, state and federal funding sources, SEPTA has funded long-deferred maintenance of critical public transit infrastructure including — for example, reconstructing track, installing power and communications systems, constructing and enhancing bridges and culverts, constructing a new terminus, building new railcar storage, and constructing new traffic intersections and access roads.

Maritime ports are significant economic engines for the national and regional economies, supporting millions of jobs, and yet, ports also are underinvested.[6] Funding for port infrastructure is derived from a variety of sources, including federal, state, and local funding, as well as private sector revenue streams. Infrastructure improvements at the Port of Baltimore, one of the East Coast’s busiest and a substantial driver of regional economic activity and job creation[7] was the focus of another successful EB-5 funding. The P3 forged between the State of Maryland and a private operator (Ports America) for the management and operations of the Port of Baltimore, required substantial ongoing private investments in cargo terminal upgrades, maintenance-related capital expenditures, crane and equipment replacement, technology improvements, construction of a warehouse and mechanic shop, and facility paving. The Port of Baltimore desired upgrades needed to service the supersized ships that could reach the East Coast after expansion of the Panama Canal. Available funding could be sourced from bonds, bank debt, private equity, and projected operational revenues from the expansion of its Seagirt Marine Terminal. However, because the state had a limited ability to issue bonds to pay for projects like the Seagirt expansion, it increasingly looked to P3s to avoid funding shortfalls. The $45 million loan to Ports America arranged by the DC Regional Center funded the increase in number of terminal berths, extension of the wharf, and purchases of new super cranes.

While the Senate and House versions of infrastructure legislation include massive amounts of federal funding for a wide array of traditional infrastructure categories — roads, bridges, public transit, rail, water infrastructure, to name a few – there also are significant provisions that target spending for rural and distressed areas.[8] Broadband investment, for example, is needed for unserved and underserved areas, which generally means lower income and/or rural. Apart from the specific allocation of $65 billion for broadband expansion to these areas, the addition of broadband to the allowable category of private activity bonds (“PABs”) could trigger very substantial additional private sector investment. Qualified PABs are tax-exempt bonds issued by local or state government to provide funding for qualified projects, a very useful funding tool in P3s. Studies show that notwithstanding billions invested by the telecom industry, the private sector is not presently incentivized to expand services to all areas.[9] Congress also is considering permanent extension of the New Market Tax Credits (“NMTC”) program, which incentivizes with tax credits the needed investment in underserved areas; a specific NMTC allocation for tribal areas; as well as significant revisions to the tax credit program for low income housing in distressed areas. Insofar as members of Congress are wrestling over among other things the total price tag on these infrastructure programs, and not the question of whether infrastructure investment is a national priority (about which there seems to be true consensus), it does appear obvious that advocates for the EB-5 investor program could be championing EB-5 investor capital as part of the solution. Simply stated: EB-5 investor capital for infrastructure. That would be most fitting, it seems, for the underserved/underinvested areas of the country.

The CMB Regional Center coordination with the IVDA, starting decades ago, led to funding of infrastructure investments at the former Norton AFB. The seed funding, along with other public and private source capital invested over time, reversed what had been a downward economic spiral. The CMB Regional Center would use multiple EB-5 investor-funded partnerships to lend more than $101 million to redevelopment of the former Norton AFB and local infrastructure projects. Through a master development agreement, the IVDA eventually handed over the development responsibilities to an established developer (Hillwood). The EB-5 investor capital was used to help fund a wide variety of infrastructure projects, including construction of the landfill hardcap for parking and related road work that would entice Stater Bros. to build its corporate office, a grocery distribution center, and cold storage facility; bridge construction and road improvements; parking for an airport terminal and hangar; drainage improvements, flood abatement, solar installations, and airport tarmac projects. The EB-5 capital investments were combined with additional project-related capital funded by state, local and federal government sources as well as private investment. These numerous infrastructure projects were the foundation and development pad that attracted major private sector investments from Fortune 500 companies, and leading manufacturers and logistics firms (including Stater Bros., Kohls, and Amazon). Saving the former Norton AFB from the economic abyss, infrastructure investments at the former Norton AFB fueled further public and private sector investments that have created some 8,800 jobs, and more than 13,800 jobs when counting the total effects.[10]

As once-in-a-generation infrastructure legislation is highest of priorities for Congress, while the EB-5 investor visa program for regional centers is also seeking an audience for its renewal, it should be emphasized that EB-5 investor capital has successfully funded priority infrastructure. It would be a mistake to overlook the opportunity to align the future of EB-5 capital investment with priority infrastructure.

*First published in October 2021 in Regional Center Business Journal

[1] Most of the economic impact references dating to the 1990s were drawn from earlier project work by economist John Husing.

[2] 2021 Report Card for America’s Infrastructure, American Society of Civil Engineers, https://infrastructurereportcard.org/ (last accessed October 1, 2021).

[3] The White House Briefing Room, Updated Fact Sheet, Bipartisan Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act, (Aug 2, 2021), https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/statements-releases/2021/08/02/updated-fact-sheet-bipartisan-infrastructure-investment-and-jobs-act/ (last accessed October 1, 2021).

[4] Infrastructure and the Economy, Congressional Research Office (Aug 5, 2021), citing to Pedro Bom and Jenny Ligthart, “What Have We Learned from Three Decades of Research on the Productivity of Public Capital?,” Journal of Economic Surveys, vol. 28, no. 5 (December 2015), pp. 889-916, https://sgp.fas.org/crs/misc/R46826.pdf

[5] Transportation Infrastructure Investment as Economic Stimulus: Lessons from the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009 (Congressional Research Service, May 5, 2020), https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/R/R46343

[6] ASCE gives maritime ports a “B-“ grade – https://infrastructurereportcard.org/cat-item/ports/

[7] The 2017 Economic Impact of the Port of Baltimore in Maryland (37,000 jobs in state generated by Port) https://mpa.maryland.gov/Documents/EcononmicimpactofPOBMaryland2017_101518.pdf

[8] See benefits for rural areas – https://www.farmprogress.com/farm-policy/whats-infrastructure-plan-rural-america

[9] The Federal Communications Commission and U.S. Department of Agriculture both administer programs aimed at extending broadband to rural communities.

[10] See reports of the Air Force Civil Engineer Center, https://www.afcec.af.mil/Home/BRAC/Norton/Norton-Today/ https://www.afcec.af.mil/News/Article-Display/Article/2051569/air-force-begins-fifth-5-year-review-of-environmental-cleanup-activities-at-for/; and for more on former Norton AFB —https://www.sbsun.com/2019/03/29/san-bernardino-marks-25-years-since-closing-of-norton-air-force-base-eyes-future/