New capital investment by immigrant investors interested in the EB-5 visa regional center (“RC”) program may be on pause while Congress puzzles out a legislative solution from historic negotiations on trillion-dollar public investments in infrastructure and social programs. Nevertheless, the petition process carries on for existing investors of private capital to remove the conditions on their permanent residence and finally settle their US immigration status. Over 11,000 petitions for removal of conditions remain pending at USCIS,[1] and approximately 3,000 more petitions will be filed in each of the next two years, unaffected by the future of the RC program. Until these I-829 petitions are approved by USCIS, the immigration status for many thousands of investors and their families remains unresolved.

Three decades running, the practice of representing investors for removal of conditions has never been easy. The practice continues to be hampered by extra-legal adjudication standards and mind-numbing processing delays, as well as the case complications arising from the misfeasance and malfeasance of managers of the businesses enjoying the fruits of EB-5 capital investment. Considering that the EB-5 visa program was designed to attract good faith investment from foreign nationals into job-creating businesses in the United States, but USCIS denies good faith investors the promised ultimate immigration benefits of the EB-5 visa program, the removal of conditions process stands out as seriously flawed.

Unfortunately, recent legislative and program reform efforts fall short, as they contemplate and emphasize new capital to be invested by future EB-5 investors and the “integrity measures” the USCIS desires to police RC program operations. It appears, in stark contrast, that nothing is on the program reform table to help those thousands of EB-5 investors who already invested in good faith – those who thus have earned their conditional status and the removal of conditions, but who have not yet finally prevailed in the complex, uncertain and protracted EB-5 application process that is not over until conditions are finally removed. Without meaningful reform from Congress or USCIS, it is foreseeable that too many good faith investors will continue to be stranded by an agency that views the immigrant’s bona fide investment as not integral to its decisions in the removal of conditions process. Good faith investors, or rather those who have not yet surrendered in the face of what they may perceive as the false promise of the EB-5 visa program, will continue to seek relief in the courts.

Courts have abundant reason to intervene considering the USCIS propensity to create new legal standards for I-829 petition adjudications. The Court of Appeals decision in Chang v. United States[2] remains a cornerstone precedent that is grounded in well-settled principles of federal administrative law. There, the Court of Appeals set aside the denial of the I-829 petition for removal of conditions where the denial was based on the retroactive imposition of a new substantive eligibility standard that did not exist when the EB-5 investor filed the initial I-526 petition, and the imposition of the new rule would cause undue burden on the EB-5 investor as compared to the government’s interest in retroactive application to the I-829 petition adjudication. At issue was agency reliance on its precedent decisions such as Matter of Izummi. A separate but often related procedural objection to raise before the court is the failure of the agency to follow advance notice and comment prescriptions for its new “legislative” rules imposed in I-829 petition cases.[3] USCIS publication of new adjudication standards in its Policy Manual, in lieu of formal rulemaking, does not usually cure either the retroactivity problem or the notice defect.[4]

Substantively, at the outset of the EB-5 visa application process, investors are required to prove the investment is “at risk” of loss in the commercial enterprise. USCIS requires a comprehensive business plan to demonstrate the intended job-creating uses of the capital invested. Thereafter, as provided in the statute on removal of conditions, the EB-5 investor must prove the investment was made and sustained. The regulation promulgated to implement the statutory standard states the agency must consider whether the evidence demonstrates the investor “has, in good faith, substantially met the capital investment requirement of the statute and continuously maintained” the investment in the new commercial enterprise. This regulation coheres with the statutory standard and just as surely arises out of the central purpose of the conditional nature of the initial period of permanent residence for EB-5 investors — to deter EB-5 investor fraud.[5] What this means, simplified, is if the EB-5 investor were to deceive by petitioning for immigration benefits without taking genuine steps to make investment capital available for potentially job-creating outcomes, the conditional period and the adjudication of the I-829 petition for removal of conditions serve to expose the absence of good faith. The statutory design of permanent residence as initially conditional for EB-5 investors, like in marriage-based cases, enables USCIS to separate out those petitioners acting without good faith. Those who do act to invest in good faith, on the other hand, should prevail before USCIS. For full context it is noted that as a rational legislative choice, Congress did not design the EB-5 visa program to require immigrant investors to “pick winners” out of the available pool of new business enterprises, a full 50% of which fail within the first five years.[6] Nor did Congress require EB-5 investors to prove, as a condition to be satisfied for full unconditional permanent residence, that at least ten jobs had been created. Before finalizing the statutory law on removal of conditions, Congress in fact clearly rejected the concept that removal of conditions requires evidence that ten jobs had been created.[7]

The relatively simple good faith formula that neatly frames what a USCIS examiner should be evaluating as the core focus in the I-829 adjudication has been ignored or elided by USCIS in numerous cases involving distressed businesses or questionable uses of enterprise assets by managers. And, with stunning consequences: Good faith investors are facing deportation before the immigration courts.

Of first significance to litigants, Matter of Izummi was an I-526 petition case; it did not consider I-829 petitions at all, nor did it consider the different body of legal standards that apply to I-829 adjudications.[8] It is therefore arguably untenable that Matter of Izummi is merely “interpretative” for I-829 petition adjudications, or that adjudication standards found in the USCIS Policy Manual are policy statements grounded in settled law for I-829 petition adjudications, when the supposed settled law is Matter of Izummi. Fast forward 20 plus years, USCIS continues to find random sentences in Matter of Izummi, take those out of context, and create new legal standards for I-829 petition adjudications.

Instead of the good faith regulation that has been law for more than 25 years, USCIS uses language from Matter of Izummi that is not specific to I-829 petition adjudications to, in effect, supplant clear and unambiguous regulations.[9] Of relevance to this writing, the Izummi case — which involved an I-526 petition and the initial design of an investment that provided for administrative fees to be withdrawn from the $500,000 investment before it was invested into the commercial enterprise (interpreted to include a wholly-owned subsidiary) – stands for the proposition that the I-526 petition cannot be approved if less than the required minimum capital of $500,000 is invested in the new commercial enterprise. In current practice, USCIS is denying I-829 petitions filed by investors for the reason that the admittedly good faith investor, who has invested a full $500,000, is unable to prove how exactly the commercial enterprise expended all of its assets. Treating a bad actor manager’s diversion of funds as some form of “derogatory information” that the good faith investor is held to rebut, USCIS finds the evidence wanting in the glow of the Matter of Izummi statement that the “full amount of funds must be made available to the businesses most closely responsible for job creation.” With this “precedent” standard as the core focus of such I-829 petition adjudications, rather than the good faith regulation, USCIS (i) tends to move the analysis well beyond the commercial enterprise that the immigrant invested in, (ii) holds the good faith EB-5 investor to account for the entire history of transactions undertaken by the commercial enterprise with other entities in order to confirm that the “same money” invested by the EB-5 investor has been used by the commercial enterprise and by the so-called “job creating enterprise” toward job-creating business activity, and (iii) loses sight of the core facts that must be proven by a preponderance of evidence. Without such proof, USCIS has found that the good faith investor has not “sustained” the investment. And for similar reasons, although USCIS professes to agree that it is the commercial enterprise that creates the jobs, USCIS has found in cases of admittedly good faith investors (and even where a sufficient number of jobs have been created), that the evidence is deficient where the investor cannot show that the petitioner’s capital investment has created the jobs.

The failure to abide by a binding regulation, as the good faith regulation is, sets up an argument in federal court for any good faith investor with an I-829 petition denial that the USCIS decision is arbitrary and capricious.[10] Or, as the government has initiated deportation proceedings against numerous good faith investors, and the legislative branch appears largely unresponsive to immigrant investor interests, the immigration courts may be tested to resolve these issues.

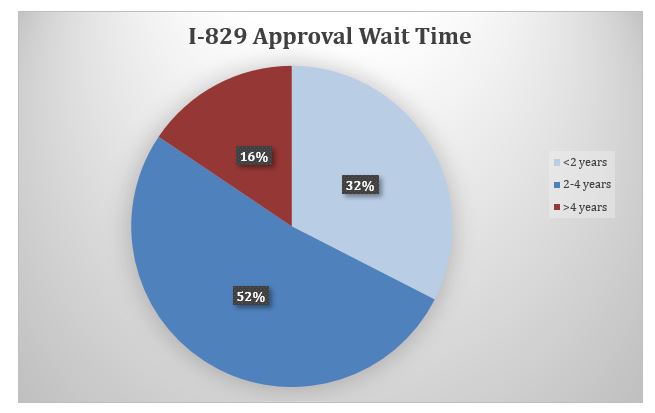

More than just an annoyance, the USCIS processing of I-829 petitions has evolved to be a form of avoidance, a poison pill of its own that tends to sap the confidence of even the most patient of EB-5 investors. Originally, as set forth in the statutory scheme, Congress had in mind a 90-day timetable for adjudication of the I-829 petition. Nowadays, USCIS states its processing times range from 32.5 to 63 months, or more than 5 years. Even putting aside one huge drawback of the EB-5 visa program that USCIS had no role in creating – the EB-5 visa unavailability at the front end for nationals of certain countries (presently, China) – the entire EB-5 process stands as a 10-year program when case processing delays are factored. Looking at actual cases, of the several hundred investor I-829 petitions approved by USCIS since 2019 through the efforts of our law practice, 68% of those clients waited more than 2 years after filing with USCIS for their I-829 petition approval. A full 16% of the clients waited more than 4 years before seeing I-829 petition approval.

Understandably, many investor clients have lost their patience. We filed mandamus lawsuits on 51 of those I-829 petitions for approved investors.

Understandably, many investor clients have lost their patience. We filed mandamus lawsuits on 51 of those I-829 petitions for approved investors.

Congress did not create the EB-5 visa category as merely an immigration pathway for immigrants who had invested in the United States, rather it designed the EB-5 visa category to attract and reward good faith investment that is at risk of loss and that truly is impactful in its potential for creating jobs that otherwise would not be created. The more than 11,000 investors and families awaiting I-829 petition approval, and the multiples of that in earlier application stages, are a reminder that the “attraction” part has succeeded. But the “reward” part has not worked out as well. In practice, the substantive and procedural hurdles for I-829 petitioners are many. As USCIS appears to have raised the bar in a growing number of cases, it is ever more clear that all avenues of advocacy must emphasize that the status of conditional permanent residence is meant as a standard review, to confirm good faith investment, along a clear and reliable track toward an end solution. As well, at the center of it all, usually, is a family desiring to fully embrace American life. Without that I-829 petition approval, however, USCIS not only holds the key to clarity about ongoing legal status but it also withholds naturalization. The full rights and commitments of US citizenship remain beyond reach. In many I-829 petition cases that USCIS seeks to deny, the evidence and applicable law support approval. Good faith investors who have kept their side of the bargain deserve approvals of their I-829 petitions.

*First published in October 2021 in Regional Center Business Journal

[1] https://www.uscis.gov/sites/default/files/document/data/Quarterly_All_Forms_FY2021Q3.pdf.

[2] 327 F.3d 911 (9th Cir. 2003).

[3] The Administrative Procedures Act requires publication of formal notice of proposed rules in the Federal Register. 5 USC 553(b),(c)(requiring advance notice of rulemaking and opportunity for comment, except for interpretative rules and general statements of policy).

[4] The failure of USCIS to follow the law of formal rulemaking for the EB-5 visa program has long been criticized. See, e.g., GAO Report to Congressional Committees, “Immigrant Investors: Small Number of Participants Attributed to Pending Regulations and Other Factors,” GAO-05-256 (Apr. 2005); Office of the CIS Ombudsman, “Employment Creation Immigrant Visa (EB-5) Program Recommendations” (Mar. 18, 2009); Department of Homeland Security Office of the Inspector General Report (Dec. 2013, OIG-14-19, p. 11 – citing inconsistencies of interpretation within USCIS).

[5] See, e.g., Regulatory Commentary: Investors are “admitted as conditional permanent residents as a means to deter immigration-related entrepreneurship fraud.” Commentary to Final Rule, 59 Fed. Reg. 26587 (May 23, 1994), quoting S. Rep. No. 101-55, at 22 (1989). As first introduced, section 204 of the Immigration Act of 1989 was entitled “Deterring Immigration-Related Entrepreneur Fraud.” S. 358, 101st Cong. §204 (1989).

[6] According to the US Small Business Administration, 50% of all new small businesses with employees will go out of business within the first five years. SBA Office of Advocacy — Frequently Asked Questions, https://www.sba.gov/sites/default/files/advocacy/Frequently-Asked-Questions-Small-Business-2018.pdf (Aug 2018), Small Business Facts https://www.sba.gov/sites/default/files/Business-Survival.pdf (June 2012).

[7] See 134 Cong. Rec. S2119 (1988), and S. Rep. No. 101-55, at 21 (1989).

[8] Compare INA 216A with INA 203(b)(5). See, e.g., Hamdan v. Rumsfeld, 548 U.S. 557, 578 (2006)(the distinct language used in different sections of a statutory scheme is intended to give effect to the distinction).

[9] Recent cases reveal courts will not condone the agency’s selective use of random language in Matter of Izummi as rationale for ignoring plain language of regulations. See, e.g., Zhang v. USCIS, No. 19-5021 (DC Cir. 2020); Mirror Lake Village v. Wolf, No.19-5025 (DC Cir. 2020); Chang v. USCIS, 289 F.Supp.3d 177 (D.D.C. 2018); Doe v. USCIS, 237 F.Supp.3d 297 (D.D.C. 2017).

[10] Under the Administrative Procedure Act, a reviewing court must set aside agency action that is “arbitrary, capricious, an abuse of discretion, or otherwise not in accordance with law.” 5 USC 706(2)(A).